-

Finding and fixing 32% misinformation in national demo

Amplifire finds and fixes 32% misinformation in national demo.

15 U.S. health systems1 participated in an amplifire demo. The demo module used a “sampler” of topics, including decision making, patient safety, and financial/administrative issues.

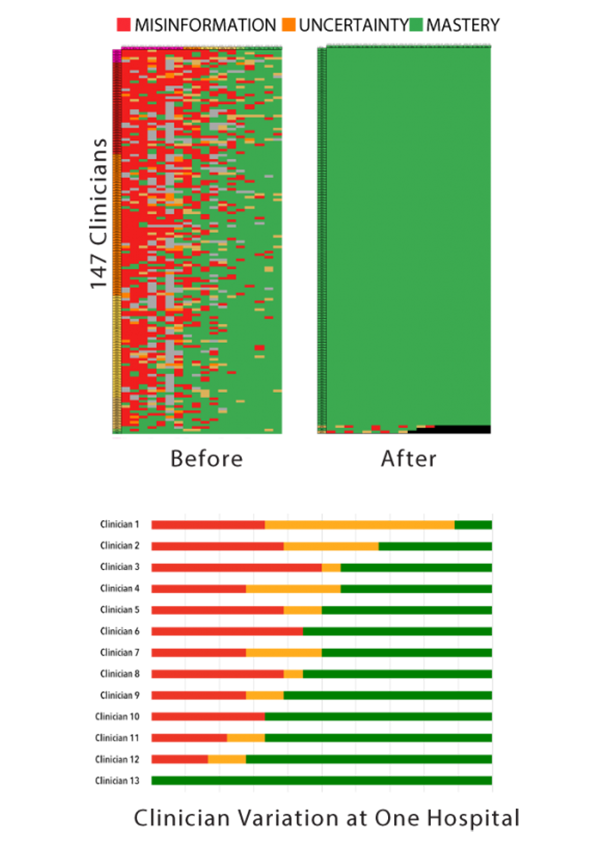

Knowledge and Misinformation: Before starting, learners knew (with confidence) approximately 50% of the material. 32% of their knowledge was Confidently Held Misinformation (CHM) which was remediated by the amplifire algorithm.

Struggle: Learners did not “struggle” with the content. 139 of the respondents showed less than 0.2 struggle. Only two learners had high struggle scores of .67 and an alarming 1.50. As a group, hospitalists are excellent learners.

Variation by Health System: Health System 4 had the most CHM (39%), while Health System 8 had the least CHM (25%).

Variation by topic: CMS Regulations had the most CHM at 48%, while Communications had only 4%.

Variation by clinician: Within Health System 1, Clinician 1 had the most CHM at 50%, while Clinician 13 had 0%.

Clinician Experience: 87% of respondents provided a rating of “good” or higher. 74% of hospitalists indicated they were likely to change how they would manage a complex patient like the one presented in the module.

1. The Amplifire Healthcare Alliance never releases identifiable data.

-

Increased pass rate on the MCAT

With Amplifire, student MCAT scores moved from the 90th to the 95th percentile.

- Over 58,000 learners have prepped for the MCAT with Amplifire.

- Students using Amplifire have answered 53,192,000 questions.

- Students have spent more than 900,000 hours of learning in

Most of the time, when people analyze the effect of an optional educational activity, they run into a correlationversus-causation problem. For example, using flash cards is associated with higher exam scores. But it’s harder to say whether the higher exam scores are because of the flash cards. It’s easy to imagine that the type of student who would make flash cards is also the type of student who would earn a high score on the exam; the flash cards might not have anything to do with it.

To avoid this problem when estimating the effect of Amplifire, we compared people to themselves. On simulated MCAT exams, learners were correct almost 15% more often when questions were related to what they encountered in Amplifire before the test (where they had no control over which concepts were tested). Completing all of Amplifire translates to several points—and a significant percentile boost—on the MCAT. For example, a learner in 2016 who would have gotten a 513 would instead earn a 516 by completing the offered Amplifire modules. That learner would move from the 90th to the 95th percentile, moving past half the students above her.

-

Increasing the pass rate on the restaurant food safety exam by 18%

Amplifire increased the pass rate on the restaurant food safety exam by 18% while reducing the failure rate by 34%.

- Industry: Trade Association

- Large food service association

- 500,000 restaurants

Every student in culinary arts must pass the food and beverage safety certificate exam in order to begin a career in the restaurant business. Their coursework usually takes place at a community college, and includes topics like Sanitation and Safety.

Amplifire’s efficacy was tested at a large community college in North Carolina with an enrollment of more than 40,000 students. Amplifire was added to the curriculum in 2015. The food and beverage safety exam pass rates were then compared with those from the year before. Students who used Amplifire were 18% more likely to pass the exam—and 34% less likely to fail it.

Learners were aware of this benefit, with 100% of them agreeing that Amplifire helped them learn and remember the material.

“It gave me the chance to see what I knew and to get help along the way.”

“Amplifire was extremely helpful, repeating the question until I was 100% sure.”

-

Telecom

Company-wide savings with Amplifire at full implementation estimated at $2.5 million per month.

- Razor thin margins and penalties for repeat truck rolls

- 1% change in the repeat truck roll rate equals an estimated

- $1 million savings per month

- Amplifire lowered the defect rate by 2.5%

Professional fulfillment companies are contracted to install satellite TV, cable, and security systems. If you’ve ever had DirecTV installed at your house, chances are that the installer was this company.

It is crucial for technicians to perform these installations and other services properly. This company pays penalties for installations that incur a service call within 30 days of its original installation or for service calls incurred on other service calls. However, they receive incentive payments if the service call rate is sufficiently low. The margin between chargeback and incentive is razor thin—less than 2% overall. As a result, for every tenth of a percent change in the company-wide defect rate, the company stands to gain or lose $100,000, monthly.

This provider began using Amplifire in combination with instructorled and on-the-job training for their new hires. Compared to employees who went through their existing training, the “amped” technician’s service rate within 30 days was a full percent lower.

In the service on service metric, the reduction was 1.5%. Once fully implemented, the cost savings to be realized are estimated as a $2.5-million-dollar boost to the bottom line…every month.

-

$4 million savings through error reduction

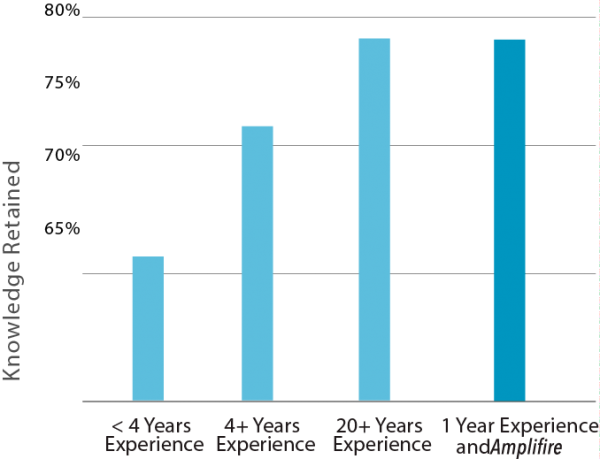

One session with Amplifire equals 20 years experience on the job.

Knowledge underlies almost every decision your employees make, from what to eat for breakfast (“I know I don’t have time to cook hash browns”) to when a particular procedure is called for on the factory floor.

Amplifire provides and reinforces knowledge, as well as how and when to apply it.

One of the largest cheese manufacturers in the world, has used Amplifire to train food-manufacturing employees for several years in a row. Before the first year of training, employees with 20+ years of experience already knew an average of 78.5% of the material. A year later, after one encounter with Amplifire, the average for all employees was 78.8%.

In other words, Amplifire was worth more than two decades on the job.

- HQ: U.S.

- Industry: Cheese Manufacturer

- Production: One billion pounds/yr

- Employees: 4,000

-

Is it Possible to Study Less, but Score Higher?

Being tested on material (rather than re-reading it) is one of the most powerful ways to improve your memory.

But classrooms today still rely heavily on reading chapters, sitting through lectures, and passively watching videos. The tests that students do encounter are designed to diagnose knowledge, not improve it.

This is a shame, because research shows that harnessing phenomena like the testing effect in the classroom can make a substantial difference in student performance.

At Amplifire, we make software that employs many findings from cognitive science—including the testing effect. As a result, the Amplifire platform significantly improves students’ performance in the classroom.

But what about the most extreme learners? Can cognitive science really make a difference to people who are also spending hundreds of hours diligently learning outside Amplifire?

We thought so, and we put this idea to the test with learners who want to become physicians and are preparing for the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). Typically, these learners study several hours per day for two months before the exam.

But how would we tell if Amplifire has an effect? We can’t have someone take the MCAT twice, once with and once without Amplifire.

Of course, we could compare people who used Amplifire against people who didn’t (called a between-subjects design). But if we saw a difference, could we really attribute it to Amplifire? There are all sorts of reasons that people who chose to use Amplifire might do better. They could be more motivated; they could have better study habits; they could have more background knowledge…it would be impossible to say whether differences in test scores were because of Amplifire.

So we came up with a different approach. We compared people to themselves.

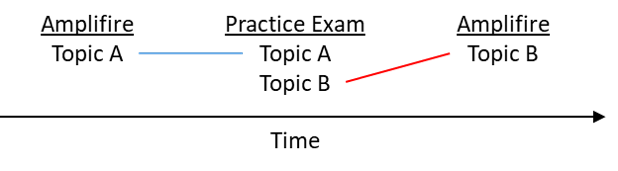

While preparing for the MCAT, learners at one of our test-prep clients encounter practice exams interspersed with Amplifire use. In a given week, they might use Amplifire on a few dozen topics. At the end of that week, their practice exam covers some of those topics and some topics that they haven’t gotten to yet. They might get to those topics the following week, or the week after.

A very simplified illustration of their experience might look like this, where a learner takes a practice exam that covers Topic A and Topic B. The learner happens to use Amplifire for Topic A before the practice exam, and uses Amplifire for Topic B after the practice exam.

Our hypothesis was that using Amplifire on a topic before a practice exam that covered that topic (relationship shown in blue) should improve exam performance on that topic. Using Amplifire on a topic after a practice exam that covered that topic (relationship shown in red) should not affect exam performance on that topic. (The benefits of Amplifire cannot travel back in time—yet!)

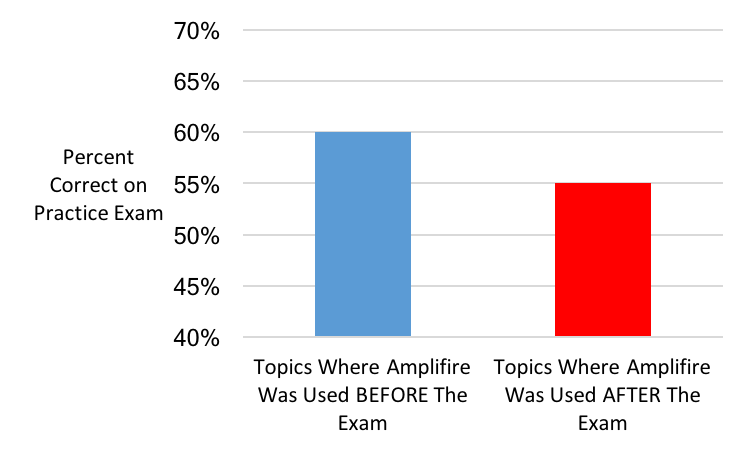

We analyzed data from 1,578 learners preparing for the MCAT and presented the findings at the 58thAnnual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society. The data supported our hypothesis:

Remember, practice-exam performance from each learner showed up in both bars. This within-subjects design means that the difference can’t be due to intelligence, motivation, education, study habits, or anything else that varies between learners. The difference is due to Amplifire.

An increase from 55% correct to 60% correct may not seem like a lot, but it translates to a reliable increase in MCAT exam score and rank. This improvement might mean getting into the medical school you want (say, Duke) versus going somewhere else (say, UNC).

This impact is especially noteworthy given all the other work that these learners were doing to prepare for the MCAT. They only spent an average of about 15 hours in Amplifire. What if they had spent 30? Indeed, what if they spent less time on unproductive activities like re-reading or watching videos, and spent that time in Amplifire instead? They might have been able to spend less total timeon test prep, but get a better score.

Stay tuned for our next post, when we describe another within-subjects analysis of hopeful lawyers preparing for the bar exam. Spoiler alert: Amplifire has a big impact there, too.

If you’d like to get your hands on Amplifire, reach out here.

-

Eight Forms of Adaptivity Your Education Technology Should Possess

While evaluating education technology, don’t forget about cognitive science. Learners deserve effective study tools, and cognitive science is the force that determines the efficacy of every education technology platform.

The complex human brain – and the knowledge variation among learners – necessitates adaptivity. Following are eight forms of adaptivity that your e-learning software should possess:

1. Selective Feedback – The first time a learner sees a module, they see all of the questions. Their answers to these questions determine what instructional material they need to see. If a learner shows that they already know something, they don’t spend another second on it. This prevents learners from wasting time.

2. Precise Timing – When a learner needs to see specific instructional material, the system doesn’t show it immediately after the question – that would impair learning. Instead, the algorithms wait so when the learner sees the material, it’s at the time that benefits their learning most.

3. Purposeful Repetition – After seeing the instructional material, the algorithms again wait for the right time to ask about that fact or concept again. Learners spend extra time where they show the system they need to, and the system makes sure that they practice until they’re perfect.

4. Smart Refresh – After completing a module, a learner will have access to full refreshers and smart refreshers. Instead of covering all of the content again, a smart refresher only covers what the learner initially didn’t know. This saves time–a learner’s most valuable resource.

5. Shadow Questions – A learner who needs another attempt on a particular topic can be given a variation of the original question, which promotes engagement and prevents memorization.

6. Content Arrangement – Content is loaded into the system in such a way that all of the above adaptations can tailor learners’ experiences. For example, if they are learning a multi-step process (e.g., factoring equations), the process is broken down into several questions. Each question focuses on a particular sub-step or group of sub-steps. This allows the software to precisely pinpoint what the learner has mastered versus where they need extra practice.

7. Learner Messaging – Real-time messages are presented to learners to improve their experience. For example, when the system detects that a learner has become disengaged, it reminds them to concentrate (and suggests that maybe it’s time for a quick break).

8. Actionable Analytics – The personalized learning continues beyond the system when instructors receive learner reports. Areas, where particular learners struggled, are highlighted, facilitating one-on-one discussions.

Transforming a static learning experience into an active learning experience is easier than you think. Learn how.

-

New Learning Strategies Can Boost Student and University Success

Ineffective learning strategies continue to plague universities across the nation. For students to perform at their highest level and for universities to succeed, these misconceptions about learning techniques and study habits must be eradicated.

Passive Learning

University students rely on outdated learning strategies, such as re-reading and highlighting, which “lead to the illusion of mastery rather than mastery itself,” according to Roddy Roediger, PhD in the book Make It Stick. Students continue to cram before exams, pulling all-nighters, hoping to master the content. While practiced widely with some success, these learning techniques fail to ensure long-term acquisition of knowledge. While students may retain the information for the short term, the material has not truly been mastered.

Struggling & Quizzing

Learning is an acquired skill, and according Roediger, the most effective strategies are often counterintuitive. New studies show learning by struggling and self-quizzing allow information to be retained longer. Students learn better when they “go wide,” drawing on all of their aptitudes and resourcefulness.

Self-quizzing is one of the most effective ways to retain information. It takes more effort than highlighting, which is exactly why it makes learning stick. This is especially effective when done before tackling a subject as it primes the mind for learning.

Spacing Effect

Rather than cramming as much knowledge as possible into a short period of time, studies by Nate Kornell and Rober Bjork, show that spacing material and revisiting it after a delay leads to long-term retention. Known as the “spacing effect,” this learning strategy requires students to “reach back” to retrieve the information. When retrieval is repeated, the mind becomes quicker at retrieving.

The amount of time that should elapse before revisiting material, depends on the type of material. Names and faces need to be revisited sooner, within minutes, of the first encounter since these associations are quickly forgotten. Then, perhaps a day or a week later, and then again, a month later.

Flash cards or highlighted notes, can be revisited after a longer timeframe once mastered. They can be revisited weekly, then perhaps monthly.

Content Mastery

Mastering any material means that it can be recalled. This statement seems obvious, but it requires conscious discipline.

Universities that recognize misinformation around learning strategies and encourage these new study techniques will see student performance and retention increase. These universities will benefit as they develop a reputation of graduating students who have truly mastered a subject. They will see an increase in student retention, performance, and alumni success making them more prestigious, and ultimately resulting in more applicants and donors.

-

The Three Most Common Mistakes in Learning

Many of the fundamental learning strategies that students consider tried and true make no significant impact on memory retention. Cognitive scientist, Henry Roediger, explains some of these common mistakes:

1. Rapid Fire Repetition

“People commonly believe that if you expose yourself to something enough times you can burn it into your memory,” explains Roediger in Make It Stick, ”Not so.” While it can appear effective, this type of learning doesn’t stick, but melts away quickly and is no longer useful down the road. Students retain more information by taking key concepts and explaining them in their own words.

2. Rereading

Roediger says, “Doing multiple readings in close succession is a time-consuming study strategy that yields negligible benefits at the expense of much more effective strategies that take less time.” Rereading essentially creates a false sense of mastery with increasing familiarity. However, this familiarity is not an indication of true understanding and often goes in one ear and quickly out the other. Students can use their time wisely by administering self-quizzes to identify what they don’t know and distilling underlying principles to those concepts.

3. Singular Focus and Intentionality

In the past, it was accepted that if you concentrate on one thing hard enough, you’ll remember it forever. As humans, we are drawn to what feels easy and productive, but that isn’t what creates retrievable and useful knowledge. Roediger says, “Skill is better acquired through interleaved and varied practice than massed practice.”