By Matthew Hays, Ph.D.

This past November, thousands of cognitive scientists from all over the world converged on Boston for the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society. The Annual Meeting is better known as the Psychonomics conference, or just “Psychonomics.” It was a triumphant return after a couple of years of COVID disruptions.

As the premier international conference on cognitive science, Psychonomics features presentations covering a broad range of brain-related topics, including bilingualism, risk tolerance, biases, and even optical illusions. Our primary focus at Amplifire was on the hundreds of presentations about learning, memory, and metacognition. (Amplifire’s founder, Charles Smith, described it as a “science buffet.”)

Some of this year’s presenters hailed from labs run by members of Amplifire’s Science Advisory Board (SAB). The SAB comprises professors who help us stay on top of the latest research. By incorporating new (and old) empirical findings into our software, we make sure that our platform is doing what’s best for your brain while optimizing the time you spend learning.

The vast majority of presentations at Psychonomics come in the form of posters. Although that might harken you back to science fairs from when you were a kid, poster sessions are actually a great opportunity to get feedback from world-class researchers about counterintuitive findings or early-stage results. Posters also offer an opportunity for up-and-coming researchers to present their own work.

We thought we’d share a few SAB-supported posters with you!

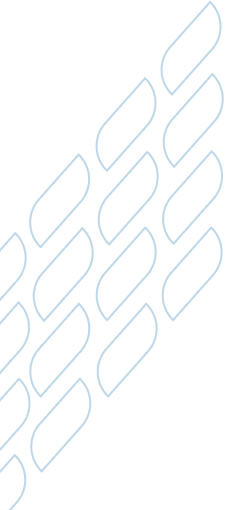

In Roddy Roediger’s lab at Washington University in St. Louis, researchers looked at flashbulb memories — vivid, enduring memories associated with a personally significant and emotional event. A couple of decades ago, the most common flashbulb memory was the 9/11 attacks; Roediger’s lab found that Gen Z most vividly remembers the night of the 2016 election, the cancellation of school due to COVID, and the death of Queen Elizabeth II. But they also found that learning about the event via social media caused the memories to be less vivid than when they were learned about through traditional media or directly from another person.

For several years, the Bjork lab at UCLA has been researching how people learn from true/false tests. Their recent work demonstrates that competitive true/false questions – questions that contain a contrast – help people learn about what the question is asking as well as what it isn’t. For example, along with other practice, the question “Eris (not Ceres) is a dwarf planet located in the scattered disc” helps people learn Eris is in the scattered disc and Ceres is in the asteroid belt. Their most recent findings show that, when students use true/false questions to learn collaboratively, the boost from a competitive/contrasting structure disappears.

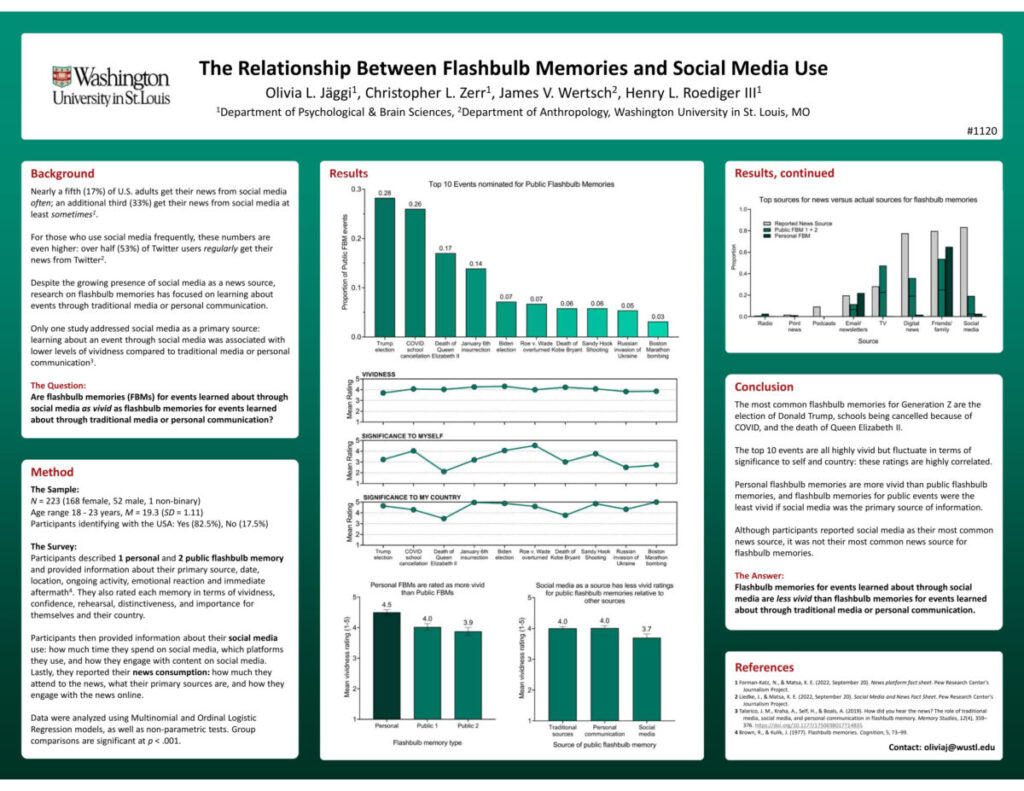

The Bjork lab is also exploring student strategies that emerged with the advent of online learning and gained popularity during the pandemic. One such strategy is speed-watching recorded lectures. I was stunned to learn that most students speed lecture videos up, and almost a fifth of them watch at double speed. What’s more, students do this despite believing that watching lectures at that rate impairs learning! And they’re right; comprehension is impaired by watching at double speed – although taking notes during the recording can make up the difference. Of course, taking notes during a normal-speed lecture is best of all.

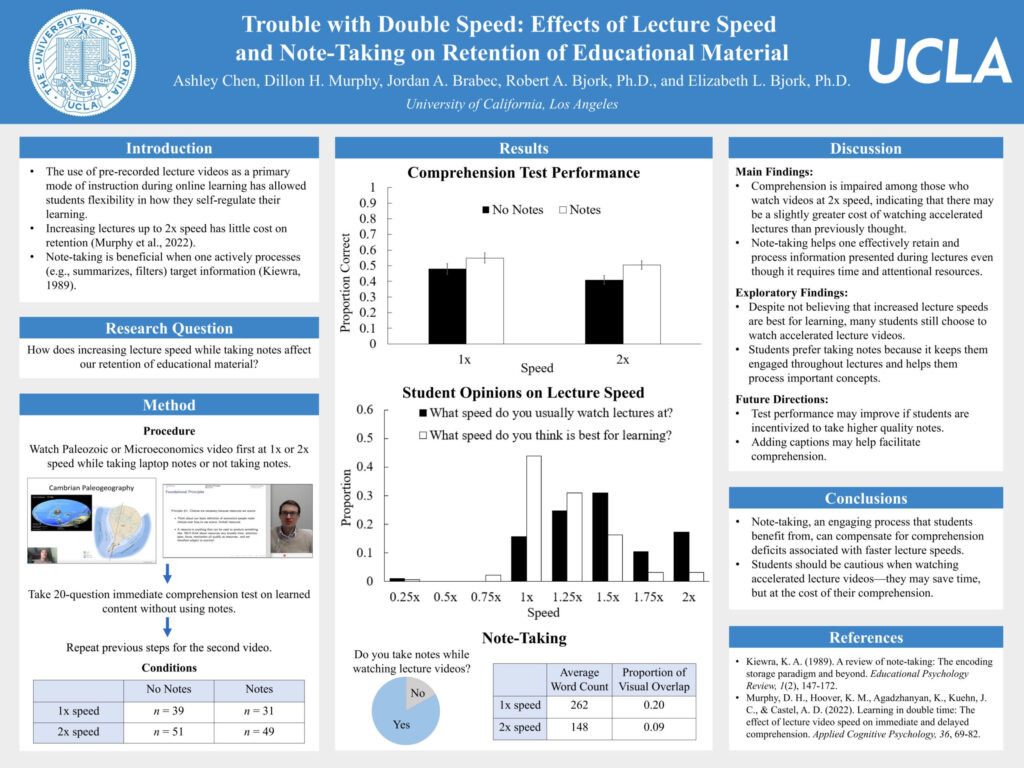

Rich Mayer’s lab at UCSB was the first to describe seductive details – parts of the learning experience that are interesting but take attention away from the elements of the experience that actually provide educational value. At Psychonomics, they explored a related concept: the extent to which being in an immersive virtual reality educational environment distracted the learners from the content (as compared to a slideshow). They found that, as a person’s individual vulnerability to being distracted increased, their learning was impaired. PowerPoint gets a lot of flak, but there was no such relationship in the slideshow condition, and learning was approximately equal from slides and VR.

The Mayer lab also has a long history of evaluating how multimedia affects learning. Previously, researchers discovered that cartoons and multimedia that create positive emotions can improve learning. At Psychonomics, the Mayer lab presented research that combined previous findings to create positive-emotion-inducing instructional cartoons. The results were promising, with substantially more learning happening from warm fuzzy cartoons than from cold black-and-white schematics.

Again, this is a tiny slice of the several hundred relevant posters, presentations, symposia, and discussions that the Psychonomic Society facilitated. More than ever before, I feel incredibly lucky to have been able to attend, and I’m eagerly looking forward to getting the gang back together in San Francisco this November.

Meanwhile, we’ve got quite a bit of science to fold into Amplifire’s software!

And, in case you missed it, check out the Amplifire Research & Analytics Team’s poster. We looked at “The Frequency of Online Learners’ Off-Task Behavior” and the extent to which COVID did – or didn’t — negatively impact online learning habits.