Over 40 years ago, at the start of my healthcare career, I was introduced to the Donabedian Model for healthcare quality. We all are familiar with this conceptual framework, consisting of three fundamental elements defining quality:

- Structure

- Process

- Outcomes

Donabedian Model:

Today, the Donabedian Model is embedded in the American healthcare system. Medicare’s quality metrics are categorized and measured as either Structure, Process, or Outcomes. To use a cooking metaphor:

- Structure consists of the ingredients and the equipment.

- Process consists of the recipe.

- Outcomes measure quality – does it taste good?

Cognitive Learning Behavior

For the most part, the way we learn has remained unchanged for centuries. Students study and then take an exam to measure what they’ve learned. And then a lot of that learned knowledge is forgotten.

Amplifire, a “knowledge engineering” platform, focuses on human learning behavior.

Technology has been used to improve the “packaging” of content being taught. While these innovations have made it easier for the teacher to teach, it hasn’t done much to help learners learn.

The cognitive science experts behind Amplifire have tackled this challenge head on. Over the past 30 years, as a result of substantial advancements in the field of brain science, we now know a great deal about how the brain encodes, stores, and retrieves information. Amplifire has incorporated these techniques into its software algorithm and demonstrated superior results in many knowledge domains, including aviation, manufacturing, and higher education.

So what does this have to do with the Donabedian Model?

I can make the case that in addition to Structure, Process, and Outcomes, KNOWLEDGE may be the fourth element of healthcare quality. Let me use the cooking metaphor again. If Julia Child and I were both cooking the same roasted chicken, and we both had the same ingredients, equipment, and recipe, her chicken would undoubtedly taste better than mine. Why? Because she has superior KNOWLEDGE, where knowledge is defined as the integration of learned information and practical experience.

Re-engineering Healthcare

As we attempt to re-engineer healthcare and improve quality by increasing the use of evidence-based practices, very little is being done to help clinicians improve how they learn and gain knowledge.

There are occasional workshops and e-learning modules. But most efforts today are directed towards using the electronic medical records (EMR) to standardize workflows, implement alerts, and provide automated decision support.

Ironically, these efforts are directed towards creating fail-safe processes that do not depend on clinician knowledge. (By the way, clinician education is still flourishing. But its focus is less on knowledge acquisition and retention and more on verifying that clinicians have taken the specified courses to meet board certification, licensure, and regulatory requirements.)

Knowledge Acquisition and Retention

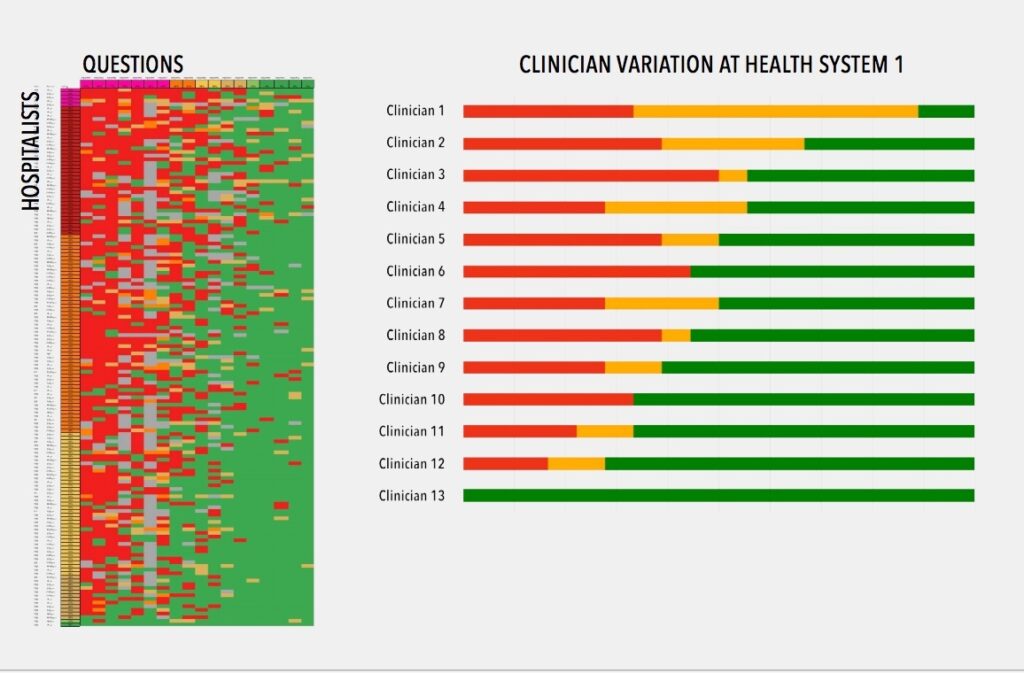

Amplifire has made a major contribution to healthcare quality by developing new ways to measure knowledge acquisition, mastery, and retention. For example, it uses colorful, adaptive heatmaps to display existing and then eradicate Confidently Held Misinformation (CHM) – those hidden untruths in the minds of your clinicians that lead to harm and loss.

With clinician-specific data, this provides a powerful new platform to engage clinicians in quality improvement. At the same time, the platform can reveal and illustrate to clinical executives exactly where there are barriers are to moving the needle on mission-critical quality metrics.

Healthcare Alliance

In the last 18 months, Amplifire has targeted healthcare as the industry that is the best match for its capabilities. The company is developing a Healthcare Alliance, engaging healthcare organizations as strategic partners, using data and collaboration to support clinicians in improved learning.

Furthermore, Amplifire recognizes that hospitalists are THE critical physicians involved in healthcare transformation. As the former Senior Vice President for the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), I am a passionate supporter of hospital medicine, the fastest growing specialty in the history of medicine. As I learned about Amplifire, I recognized that it is a tool that can support hospitalists in their efforts to improve quality, safety, and patient experience. I am working with the company to educate hospitalists about the power of this knowledge engineering platform.

Hospitalist Pilot Study

A recent Hospitalist Pilot Study conducted by Amplifire focused on a mixture of clinical content, patient safety, and administrative content. The results indicated that learners knew (with confidence) 50% of the material. However, 32% of the content represented Confidently Held Misinformation (CHM). Over 69% of learners indicated they preferred Amplifire’s educational experience.

Knowledge Engineering Solutions

It may be audacious to suggest KNOWLEDGE as a fourth element to the Donabedian Model, a paradigm that has a sacred place in the healthcare industry. Perhaps KNOWLEDGE transcends or integrates the other three elements.

In any case, there is no doubt that improving hospitalist knowledge has the potential to improve healthcare quality.

Specifically, the study of 1,984 patients admitted to hospitals between 2008-2012 found that patients admitted during an unannounced Joint Commission survey had lower 30-day mortality rates than those patients admitted three weeks before or after the unannounced survey. The JAMA study’s authors said the most probable reason for the decrease in mortality during survey weeks is the “heightened scrutiny during visits” and the physical presence of surveyors, similar to how the Hawthorne effect contributes to better hand hygiene compliance.

Why is this study important? At first glance, it looks like it touts The Joint Commission as the long arm of the law and that hospital staff fall in line and take the best care of patients when being off their game could get them in trouble. In other words, the fear inspired by Joint Commission surveyors brings out the best in hospital staff.

Really? So what are we to do with this finding? Are we to extend greater superpowers to The Joint Commission to instill more fear, more continuously in hospital staff so that patients are safer? To do so would require a constant TJC presence in hospitals. How is that possible? More surveyors? More frequent unannounced surveyors, or 24/7 drone surveying? Deputized hospital staff to serve as whistleblowers? More real-time access to quality and safety data by TJC to monitor when things may be going wrong and swoop in with tasers?

The abiding question is whether fear is a sustainable motivator for performance. This study would suggest that fear works. But if you’re like me, when I’m in a state of fear, I seek the comfort of authority, I don’t trust my own judgment, I don’t use my peripheral vision, and I get frustrated by the sense of oppression. So, the REAL question from this study isn’t how we get more Joint Commission in healthcare; it’s how do we liberate healthcare from The Joint Commission to perform well without fear.

An antonym of fear is confidence. Today’s physicians and healthcare professionals have every reason to be afraid and every reason to lack confidence. Every decision made for patients is scrutinized by payers, regulators, and risk underwriters, with harsh consequences. Professional judgment is being codified into guidelines and standards of care because rogue physicians may go “off book” when caring for patients. Metrics are imposed on physicians that are supposed to represent “quality”, and performance against them is publicly reported, not to mention financial penalties levied on those whose numbers don’t measure up. In other words, doctor, we don’t trust you.

But just because you are confident doesn’t mean you’re correct. Just as being correct isn’t of great value if you don’t act on it with confidence. The answer would seem to be that physicians and staff being Confident AND Correct is the best way to ensure performance. In an industry that is utterly dependent on knowledge, being Confident and Correct when making care decisions is the best alternative to an oppressive Draconian system of regulatory oversight and fear-based motivation.

Prolific advances over the last 25 years in the brain science of how people learn and remember now make it possible to embed knowledge in people and commit it to long-term memory, at scale, without relying on extraordinary teachers available 24/7 or an oversight process that scares people into learning and remembering. I am not suggesting that physicians are infallible or that they know more than they do. In fact, in our work using Amplifire in healthcare so far, most physicians are confident and incorrect about 25-35% of what they need to know, and that needs to be and can be corrected.

Correcting misinformation is ultimately what The Joint Commission’s job is. But the JAMA article’s suggestion that beefing up The Joint Commission’s presence in hospitals to keep staff motivated to do the right things right more often is neither scalable nor sustainable. Offering hospitals and physicians a scalable way to stay current and continuously fend off misinformation so that physicians are both confident and correct is the best pathway to improving healthcare performance.

In the 1991 film called Defending Your Life, Albert Brooks plays a recently deceased man who is in a celestial weigh station where people defend the quality of their lives on earth as a way to make the case that they are worthy of advancing to the next level of existence in the universe. Brooks’ defense attorney Rip Torn explains to Brooks that, “the point of this whole thing is to keep getting smarter, to keep growing, to use as much of your brain as possible. Fear is like a giant fog, it just sits on your brain and blocks everything—real feelings, true happiness, real joy, they can’t get through that fog. But if you lift it, buddy, you’re in for the right of your life.”

That seems confident and correct to me.