This blog is the last of six installments in the “Learning and Memory” series that investigates the science behind learning. Each blog is a bite-sized version of articles written by Amplifire’s chief research officer, Charles Smith. To read the full article, follow the link to “Motivational Triggers for Learning.”

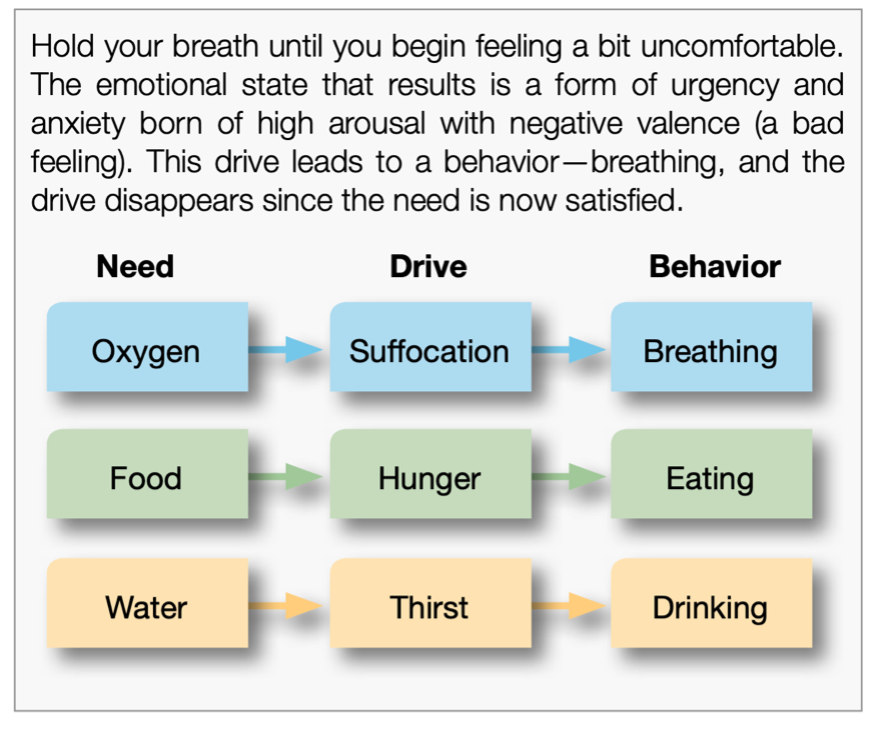

As humans, we are motivated to act for a variety of reasons. If our bodies need food or water, the sensation of hunger or thirst drives us to eat or drink. Our bodies need oxygen, so if you try to hold your breath, the sensation of suffocating drives you to breathe. But to the procrastinator, the will to complete a task sits on the back burner without a clear motivation. So, how does one “find” motivation?

So far, we’ve discussed cognitive and emotional triggers for learning. The third element of the triparte self is motivation, of which neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux describes as a “neural activity that guides us toward goals and outcomes that we desire and for which we will exert effort.” Unfortunately, many students find themselves lacking the motivation to learn, but this lack of motivation is not entirely their fault. Our education system is not complementary to the ways people learn best. Motivation readily exists in our minds, we just have to trigger it.

If motivational triggers could be better used in learning situations, they could help students make learning stick.

How does motivation work?

On a molecular level, motivation is generally facilitated by the neurotransmitter called dopamine. While many people associate dopamine with pleasure, it is actually responsible for kickstarting pleasure by prioritizing human attention and interest. Imagine pleasure as a pathway with a start and an end, and imagine dopamine as the journey between both points. Dopamine levels are at their highest during the anticipation stage, allowing humans to focus and pay attention to a particular stimulus and tune out the rest. Dopamine is the chemical that creates our sense of motivation and compels us to a certain (happy/pleasurable/satisfactory) end.

So how can dopamine be successfully triggered in a learning scenario? First, we must understand how we, as humans, are naturally motivated.

Why is motivation important for learning?

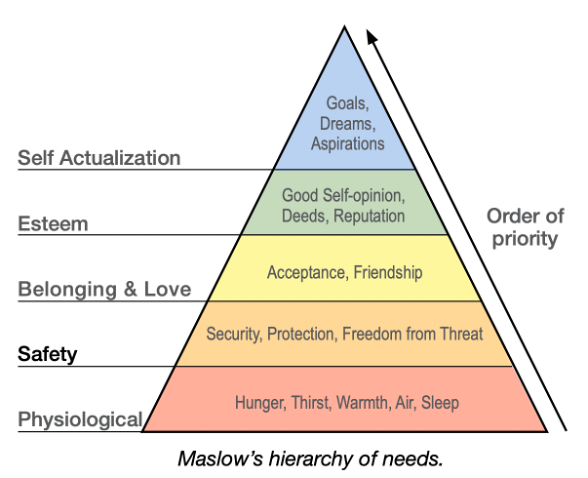

Like cognition and emotion, motivation is a neurological mechanism that helps humans interpret and interact in the world successfully. Motivation to satisfy basic biological needs is only the preliminary stage and leads to the motivation achieve the pinnacles of human aspiration. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs illustrates stages of motivation:

Motivational drives are created by negative bodily states in which a biological need (like hunger) creates internal feelings called drives that lead to behavior that aims to reduce that need. Humans share the sensation of motivational drive with all animals. Here are some examples you’ve seen in the introduction:

Motivational incentives take drives to the next level of sophistication. Humans have a nearly limitless ability to generate incentives, whether extrinsic, like the reward of good grades compelling a student to work hard in school, or intrinsic, like reading a novel, traveling, or exercising.

Motivational goals are future-based aspirations. People who exercise this type of motivation often exhibit better performance. Human’s ability to place value in the wellbeing of our future selves is a major evolutionary differentiator. This capability is what allows us to weigh what is immediately satisfactory against what benefits us more in the long run.

Motivation compels us to acquire the necessary information to get us from when we are to where we want to be or what we want to do. Understanding the motivational feedback loops can help us channel these drives, incentives, and goals into long-term learning.

5 types of motivational triggers to improve learning and memory

Finding the motivation to learn can be hard, especially in a world with endless distractions. In the face of distractions, we don’t process new information as well as we could, and that information isn’t stored correctly, thus affecting our ability to recall what we’ve learned in the future.

The good news is that humans have motivation hard wired in our mind. The sense of motivation is naturally built into our brains, we just have to tap in. Here are a few powerful motivational triggers — used by us here at Amplifire — that are proven to improve the effectiveness of learning by creating stronger memories:

1. Curiosity

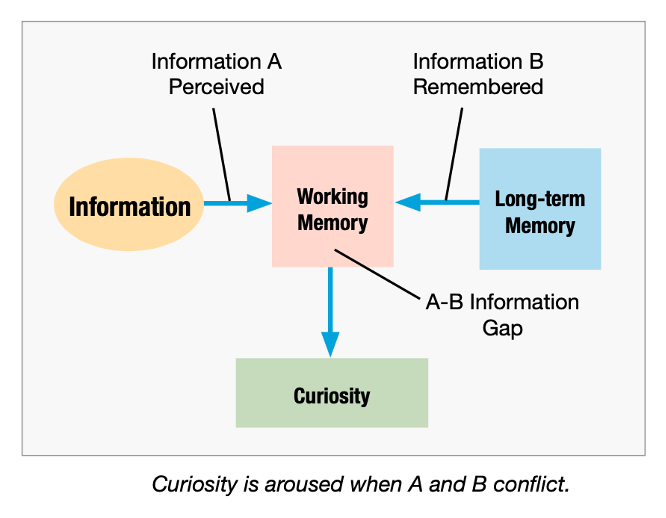

Curiosity is the drive that closes the information gap. We’ve all heard the expression: curiosity killed the cat. However, in reality, the opposite is true. Cats’ strong sense of curiosity allows them to be so in tune with their surroundings that they can identify danger with astonishing ease. By constantly investigating, cats can more easily identify what is normal and what is new and rectify any discrepancies.

Psychologists call these discrepancies information gaps. Information gaps can be simulated or called out in learning situations to stimulate curiosity — a heightened state of learning. Through a sense of curiosity, one closes the information gap, doubts are eliminated, and learning occurs!

2. Rewards

Reward is the classic motivator. Perhaps you’re familiar with an experiment conducted by Russian psychologist, Ivan Pavlov, who conditioned dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell, with the anticipation of a reward of meat. While the human mind is more complex than a dog’s, we, too, respond strongly to rewards.

Rewarding has been found to be most effective as a learning tool when the recipient is uncertain about the ratio in which rewards are given — when they seem to occur randomly. The unpredictable nature of the effective reward system keeps the brain on its toes, and keeps the learner invested in the outcome.

3. Uncertainty and Risk

Uncertainty and risk create a circumstance that causes dopamine levels to rise, thus sharpening focus and attention. Moderate risk is one of the great motivators. Risk-taking is a powerful emotional trigger for a range of creatures because organisms that made the best bets were rewarded when the bets paid off. This explains why calculated risk feels good. As long as uncertainty does not start to create feelings of fear, it will help motivate learning and create long-term memory through arousal and attention.

The key point is that learners are motivated to go back for more of the mental charge they felt from a moment of uncertainty and risk, and they learn deeply in that state. Teachers — and teaching tools — can create this scenario in a learning situation to hold students’ attention, thus resulting in higher-quality learning.

4. Progress and Optimism

Progress and optimism are highly correlated with learning and achievement. We are wired to feel best, learn well, and perform productively when we are making progress towards attaining our goals. This motivation has proved important from an evolutionary standpoint, and it’s no coincidence that education in both western and eastern traditions has emphasized personal improvement through the power of knowledge, self-discipline, hard work, and perseverance in the face of adversity.

In one study, English speaking students in a poor, inner-city setting struggled learn how to read. No matter what techniques were used. Then, researchers tried again, using Chinese characters instead of English words. Miraculously, within a few hours, the students could read Chinese sentences better than they read English. This change in perspective revealed that students’ previous negative experiences with parents, the educational system, and general social circumstances of failure had left them inherently pessimistic. This pessimistic mindset associated with their familiar language prevented them from learning, whereas a new perspective allowed for optimism, and resulted in rapid learning.

The evidence for optimism’s effects on learning is unequivocal. Students with higher levels of optimism and positive explanatory style regularly perform at higher levels than their “talent” (as measured by IQ and SAT scores) would indicate.

5. Games

Game playing is observed in all mammals, especially the young, and causes effortless learning. If you’ve ever seen a nature discovery show, or even observed young animals in the wild, you’ve seen babies explore their place in a social hierarchy, hunt for food (or avoid becoming food), find a mate, and successfully reproduce through playing. The desire for fun and games is how nature inspires creatures to practice, learn, and remember to prepare us for successful lives.

Today, gaming companies utilize the services of neuroscientists and psychologists who are fully aware of the role of dopamine, reward schedules, mirror neurons, evolutionary psychology, and uncertainty in motivation and behavior. The gaming industry is worth more than $300 billion in 2022. Applying the psychology of gaming to education, rather than just recreation, creates a powerful learning tool. Rather than generate revenue, games could cultivate stronger, more knowledgeable minds!

Interested in investigating more motivational learning triggers? Check out the full research article “Motivational Triggers for Learning” for more cognitive science discoveries, theories, and scenarios.

From the beginning, Amplifire has relied on innovative brain science to guide its product development to create the most effective learning and training solution, perfectly tailored to the way the human brain works. Learn more about how Amplifire helps people learn better and faster by checking out a demo.